The Archaic Period at Spring Lake

According to Collins (1995, 2004), the Archaic stage in Central Texas lasted approximately 7500 years, from 8800 to 1200/1300 BP. He has divided the stage into Early, Middle, and Late Archaic based on Weir’s (1976) chronology. The Archaic stage is characterized by several transitions including a shift in hunting focus from Pleistocene megafauna to smaller animals, the increased use of plant food resources and use of ground stones in food processing, increased implementation of stone cooking technology, increased use of organic materials for tool manufacturing and an increase in the number and variety of lithic tools for woodworking, the predominance of corner- and side-notched projectile points, greater population stability and less residential mobility, and systematic burial of the dead. The markedly increased emphasis on organic materials in tool technologies and diet is likely a reflection of preservation bias.

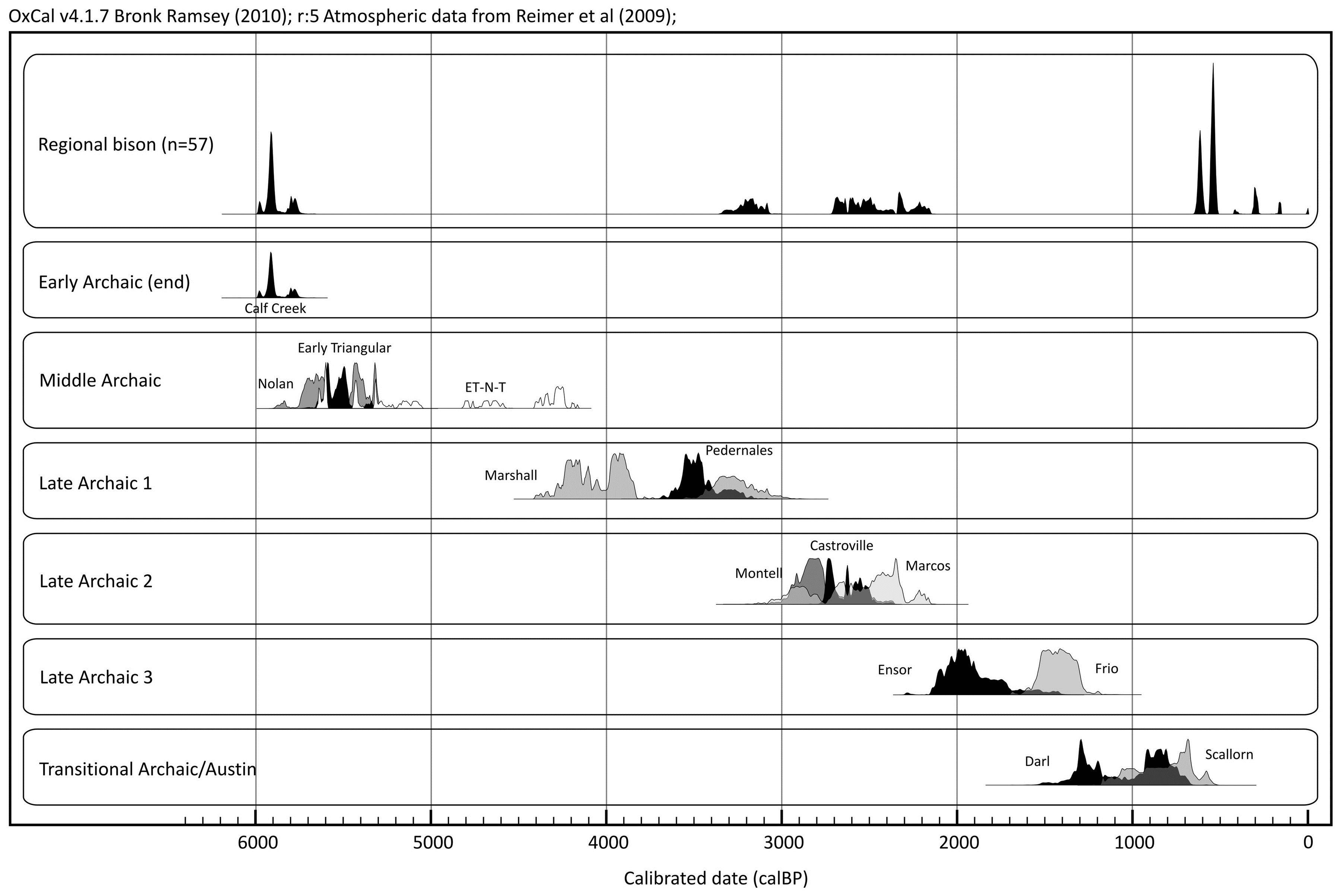

Traditionally, scholars define the end of the Archaic period by the appearance of bow and arrow technology around 1200 BP. However, Lohse and Cholak (2013) argue that this shift, while important, was relatively insignificant in comparison with other evidence for strong cultural continuity until approximately 650 years ago (Figure 4). Accordingly, we currently consider the Archaic period as the 5,000 years encompassing the end of the Early Archaic to the beginning of the Late Prehistoric Toyah interval. This range is based on the timing of projectile point styles, sporadic periods of bison hunting, and, to a lesser degree, some environmental conditions in the region. The Archaic starts with the Calf Creek horizon (including Bell and Andice types), representing the terminal Early Archaic, and ends with Scallorn.

Calf Creek Horizon

Much of the recent archaeological work at Spring Lake has been devoted to the large, well-defined and relatively intact Calf Creek component. Because this temporal horizon, which is dated to between 6000 and 5750 years ago, is not well understood, the deposits at Spring Lake may prove vital to our understanding of this dynamic period in Texas Prehistory.

Click the image above for more information about the Calf Creek Horizon at Spring Lake.

Early Archaic Period

The Holocene marked a significant climate change associated with the extinction of megafauna, which stimulated a behavioral change in land use. Early Archaic groups focused more intensively on the exploitation of local resources such as deer, fish, and plant bulbs. This dietary adjustment is evidenced by the increased number of ground stone artifacts, burned-rock middens, and wood-working tools such as Clear Fork gouges and Guadalupe bifaces (Turner and Hester 1993:246–256). Projectile points are dominated by bifurcated or split-stem morphologies that often grade into one another in terms of style and design. Dillehay (1974) argued that bison were widely available across Texas, although confirming data are often lacking.

The end of the Early Archaic dates to ca. 5750 B.P. (Lohse and Cholak 2013). This date places the wide-spread Calf Creek horizon, a brief period closely associated with bison exploitation across the Southern Plains (Wyckoff 1994, 1995) at the very end of the Early Archaic. This placement reflects the close stratigraphic association at nearby Spring Lake of Calf-Creek-related point types (Bell and Andice) with bison remains as well as immediately preceding types in the regional sequence, including Merrell and Martindale. These two types are typical Early Archaic forms in Central Texas, while the Calf Creek horizon is very poorly dated here; this component at Spring Lake may represent the best known instance in the entire state.

Middle Archaic Period

The Middle Archaic in Central Texas dates from 5750-4200/4100 and is generally associated with the Altithermal, a prolonged period during which the climate fluctuated from arid to mesic, then back to arid in Central Texas. Vegetation and wildlife regimes all fluctuated in response to these environmental oscillations, with human groups responding accordingly. Large ungulates (bison) are absent from the record during this time. The Middle Archaic is characterized by two primary projectile point style intervals: Early Triangular (Taylor and Baird types), and Nolan and Travis. Taylor bifaces are broad and triangular, similar to the earlier Calf Creek Styles, but lacking any basal notches. By the latter part of the Middle Archaic, Nolan and Travis points predominate; both are technologically and stylistically dissimilar to the preceding styles (Collins 1995, 2004). The Nolan-Travis interval was also a period when temperature and aridity were at their peaks. Prehistoric inhabitants acclimated themselves to peak aridity as seen through increased utilization of xerophytes such as sotol (Johnson and Goode 1994). These plants, typically baked in earthen ovens, also reflect the development of burned rock middens. During more arid episodes, the aquifer-fed streams and resource-rich environments of Central Texas were extensively utilized (Story 1985:40; Weir 1976:125, 128).

Late Archaic Period

The Central Texas Late Archaic spanned the period of ca. 4200/4100-1270 BP. Bison returned episodically to the southern Plains (Dillehay 1974), strongly influencing subsistence during periods of visibility. Cemeteries at sites such as Ernest Witte (Hall 1981) and Olmos Dam (Lukowski 1988) provide some evidence that populations increased and that groups were becoming territorial (Story 1985:44–45), although this pattern had begun by ca. 6,500-7,000 B.P. (Hard and Katzenberg 2011; Ricklis 2005). Numerous projectile point styles during this period suggest increases in population pressure and social and technological divisions between bands. Common styles include Bulverde, Pedernales, and Marshall (Late Archaic 1); Montell, Castroville, and Marcos (Late Archaic 2); and Ensor, Fairland, and Frio (Late Archaic 3). The Transitional Archaic and Austin periods, together, represent the last phase of Archaic lifeways in the region. Except for the gradual (and poorly dated) appearance of the bow and arrow, subsistence practices, settlement patterns, and technological behaviors appear to change slowly throughout this period (see Black and Creel 1997; Houk and Lohse 1993). Point styles that define this final transitional interval include Darl and Scallorn. Burials from this time reveal a high proportion of arrow-wound deaths (Black 1989; Prewitt 1974), perhaps suggesting some disputes over resource availability.